The art of Olga Stozhar, in this case, her ‘They are Looking at Us’ project, is dedicated to the memory of Elie Wiesel as a means of guaranteeing that German democracy can, despite the threats that it faces, persist. Aleida and Jan Assmann, recipients of the Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels, are to thank for articulating the difference between a "communicative type of memory" provided by people with first hand experience in contrast to a symbolically-loaded "cultural memory" that those born after the fact uphold, a distinction that has impact in our day and age.

The art that Olga Stozhar realises provides is an essential contribution to the common cultural memory that is part and parcel of the definition of post-war democratic Germany. Stozhar's project deals with the dignity of the murdered Jews, ergo human dignity in general, as detailed in the German Basic Law which is the backbone of German democracy.

Article 1 of the German constitution clearly states that "human dignity" is the foundation for all laws and all acts carried out by the state to maintain law and order. The crux of the cosmopolitan philosophies of the Enlightenment, especially as represented by Immanuel Kant, postulate, as Kant did in the Metaphysik der Sitten (The Metaphysics of Morals) "So act as to treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of any other, in every case at the same time as an end, never as a means only."(1)

The perception of a human being as an end on to himself means that the person is perceived in at least three encompassing dimensions: acknowledged as existing and tolerated, which entails not only having a right to bodily integrity and a personal identity but also belonging to a socio-cultural group. This acknowledgement corresponds to not permitting the humiliation of human beings. Forbidding the humiliation of human beings is based on the each person 's own sense of self-respect and the dignity, bearing testament to a person respecting himself. This self-respect is infringed upon when control over people's bodies is taken away from them. This can also be defined as when they, as human beings who can talk and express themselves, are not paid the respect deserved, not taken seriously as a group or in referring to the social context from which they hail, are belittled or treated disrespectfully. These breaches manifest itself themselves when, for example, victims are humiliated, causing them embarrassment.

In the Jewish Italian chemist, Primo Levi's sober report of his internment in Auschwitz, he detailed experiences in which he was utterly deprived of the most basic dignity. On 26 January 1944, Levi wrote, one day before the liberation of the concentration camp, "It is man who kills, man who creates or suffers injustice; it is no longer man who, having lost all restraint, shares his bed with a corpse. Whoever waits for his neighbour to die in order to take his piece of bread is, albeit guiltless, is further from the model of thinking man… or the most vicious sadist". (2)

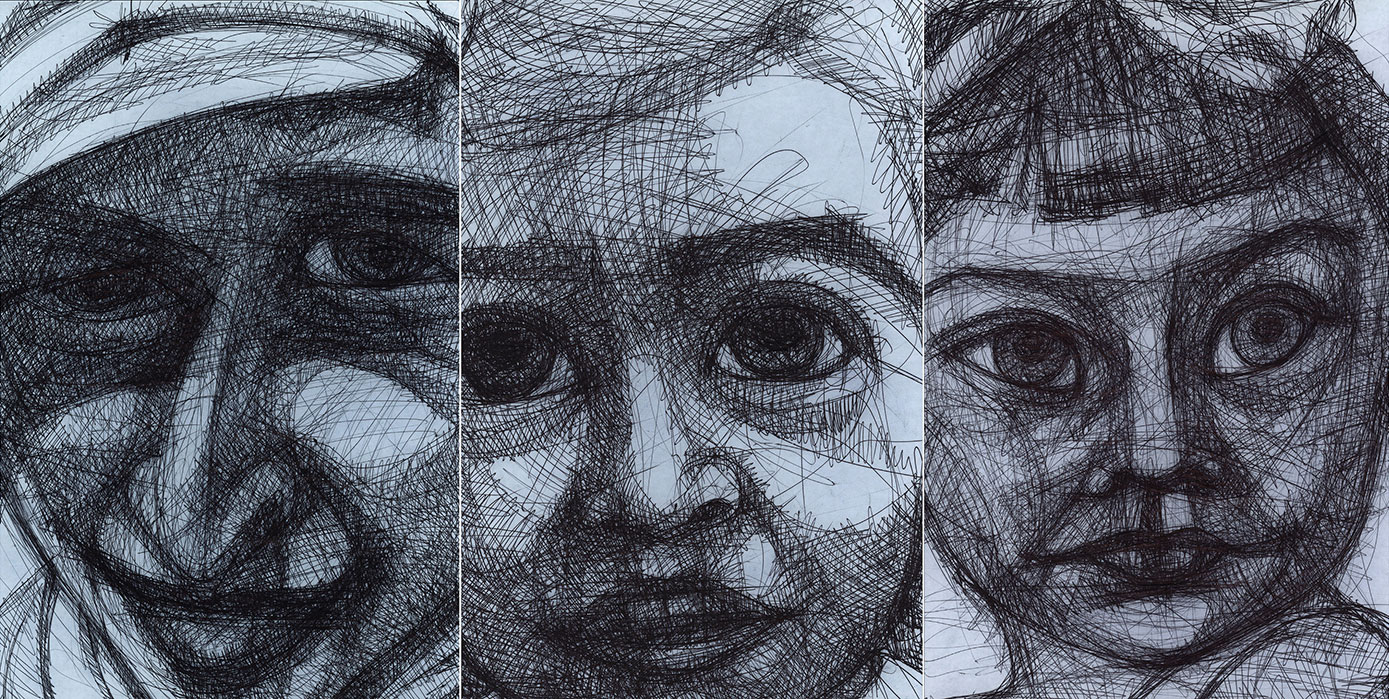

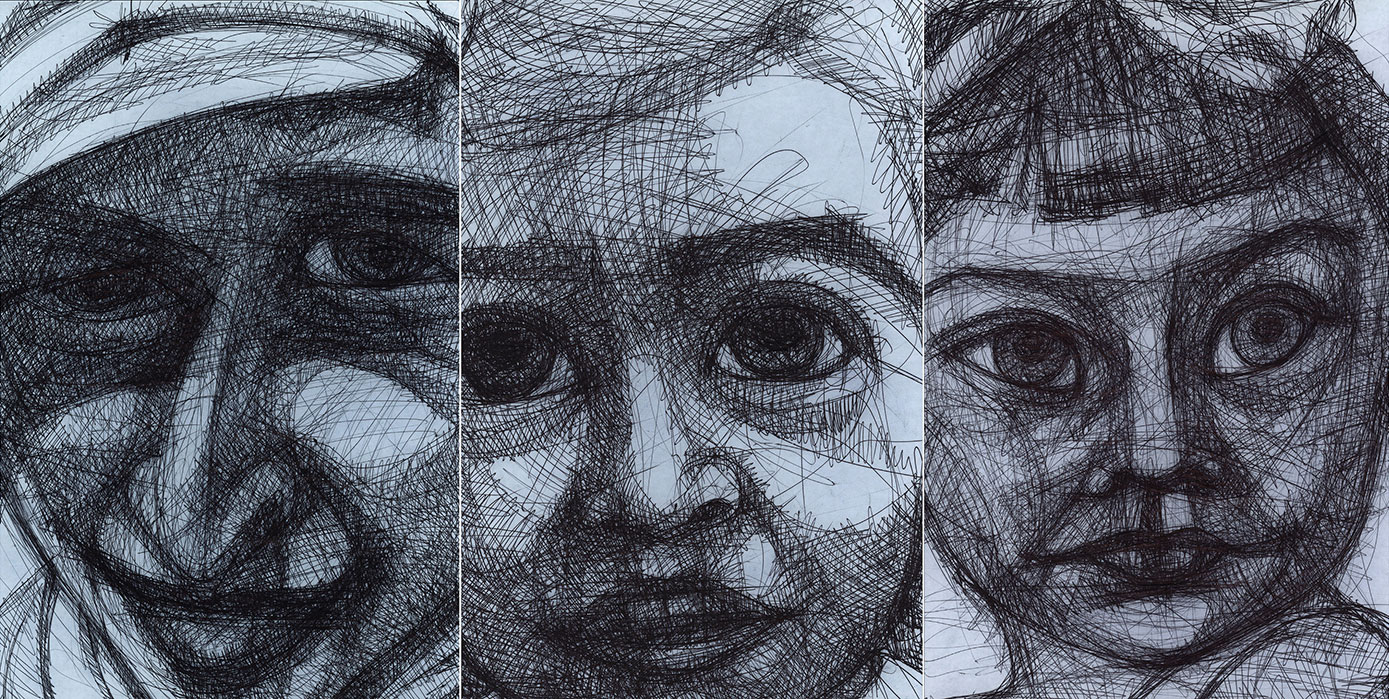

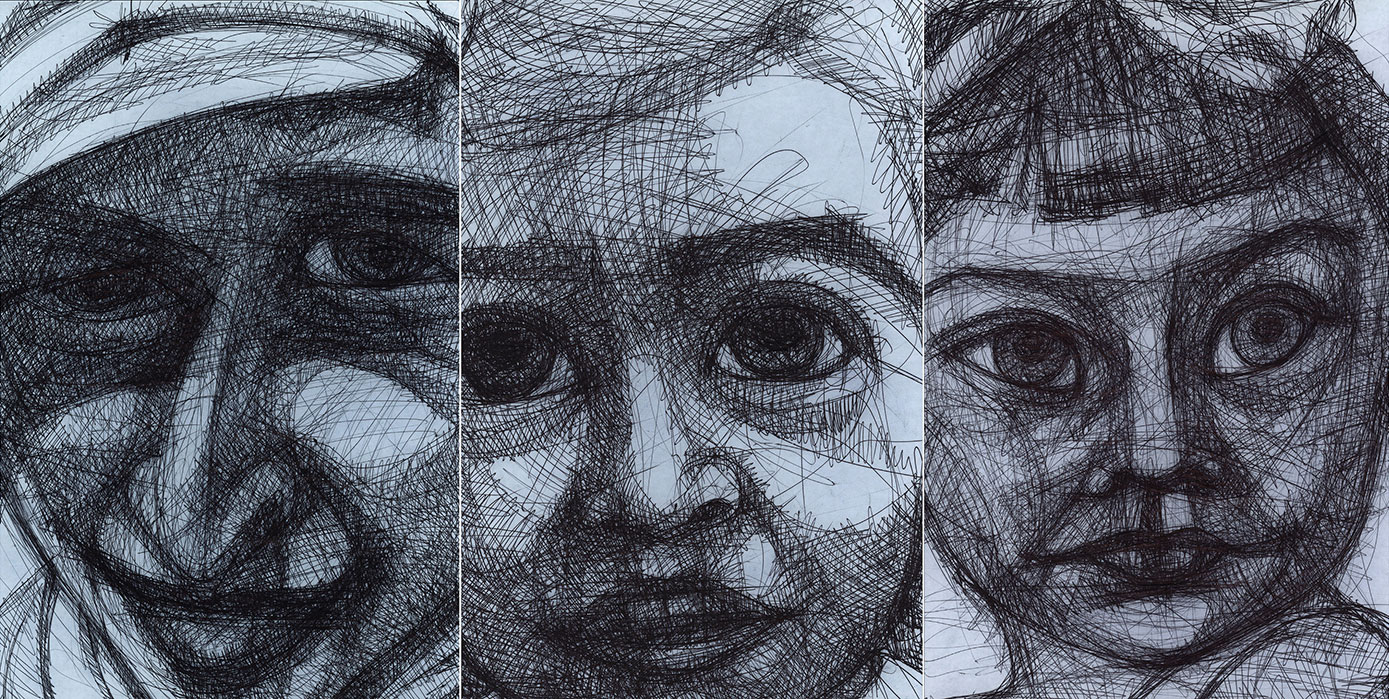

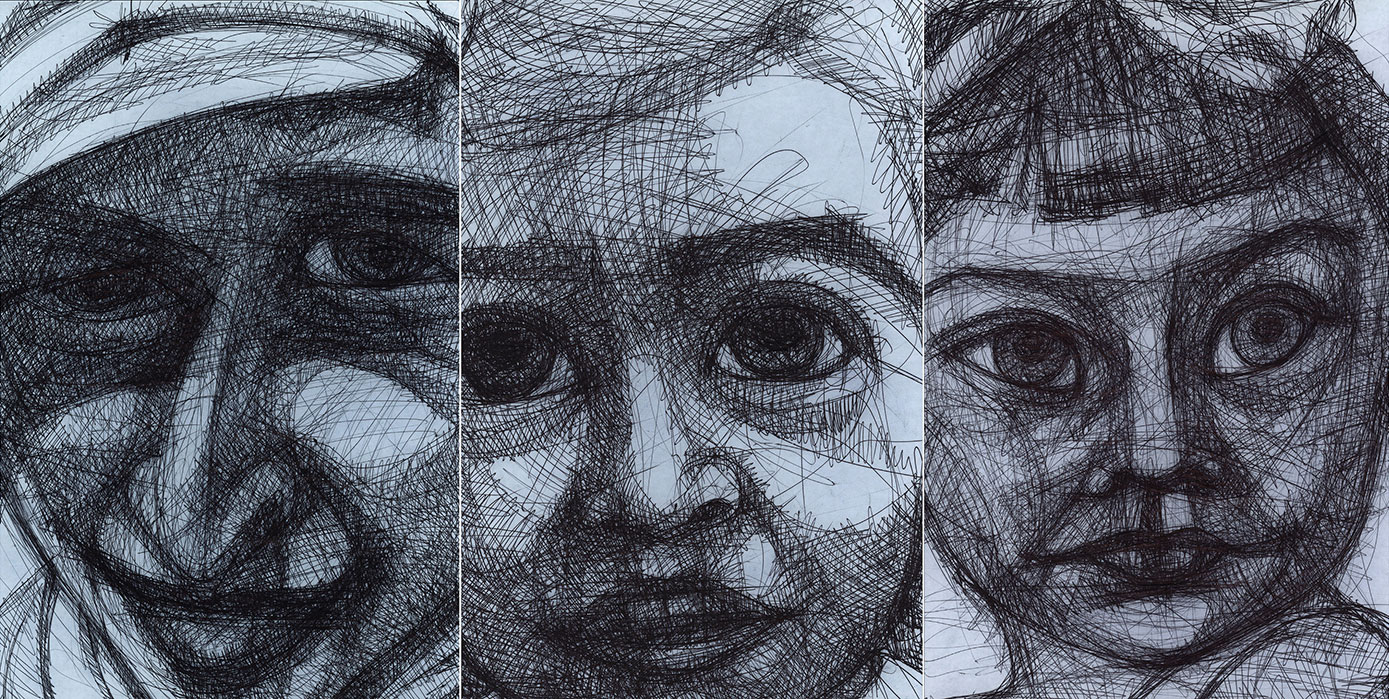

Stozhars' project, ‘They are Looking at Us’ expresses, in a different way, what Primo Levi meant. The lack of dignity that the victims experienced is not what is shown. Putting faces to a mass of victims, giving them their countenances back in a literal sense is at the heart of her project. By carrying out laborious, meticulous work with photographs of victims, Olga Stozhar relays emotion in a manner that stands out. She has realized thousands of elaborate pen drawings, referring to the countless individuals who were murdered. These works postulate precisely, as the Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, who survived the Nazi era by fortunate accident, wrote in his unparalleled philosophical texts that the face of the other, indeed, the face of the suffering of someone else, is the trace that shows us the path to God. And the divine commandment is: Thou shalt not kill!

Olga Stozhar's ‘They are Looking at Us’ project precisely manifests this idea in artistic form. In a transitional period in time, from communicative memory facilitated by survivors to the cultural memory of the following generations, such work is an imperative.

Prof. Dr. Micha Brumlik

(1 ) from Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals, Immanuel Kant, English trans. Thomas K. Abbott, with revisions by Lara Denis (G4:429)

(2 ) from If This is a Man., Primo Levi, English trans. Stuart Woolf (p. 177-8)